The latest ‘Countdown’ newsletter from the Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller Center for Zero Carbon Shipping (MMMZCS) reminds the industry that in spring 2025, the Member States of the IMO will decide on historic regulations for GHG emissions from international shipping.

These mid-term measures will, according to MMMZCS, either be a turning point and drive decarbonisation of the industry — or fail to meet the ambition of the IMO strategy and lock in fossil fuel use.

The Centre has made key recommendations for policymakers to consider during IMO negotiations:

- Support an effective reduction pathway for the Goal-based Fuel Standard (GFS): Be ready to refine emissions limits per unit of energy (gCO2eq/MJ). To be effective, the GFS must have a strict reduction pathway with progressively tightening intensity targets, exposing a growing share of emissions to a penalty.

- Set the right penalty levels: Ensure a high penalty to raise the cost of non-compliance and incentivize overcompliance. The share of fossil fuel emissions subject to a penalty and the level of the penalty largely determine the business case for sustainable fuels.

- Account for GHG pricing: Understand the implications of GHG pricing and its role in mobilising revenue – and gear up for discussions on how best to disburse these funds.

- Ensure the right scope: Support measuring emissions on a WTW basis, in line with the IMO strategy.

The IMO is tasked with setting global standards and regulations for the international shipping industry on safety, security, and the environment. It creates regulations that its 176 Member States implement in national law. Countries that have ratified the IMO’s conventions, such as the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL), are obligated to enforce these rules, giving the IMO significant global regulatory power.

In 2023, IMO member states agreed on a revised GHG strategy. The strategy calls for substantial and lasting reductions in emissions of GHGs contributing to the climate crisis: carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH3), and nitrous oxide (N2O). These emissions are typically reported together in terms of carbon dioxide equivalents (CO2eq). As global economic growth depends on shipping, GHG cuts must happen alongside the continued growth of the shipping industry.

The new IMO strategy outlines the target GHG emission reductions for the shipping industry. However, meeting these targets will rely on effective regulations. Global environmental regulations have proven effective in the industry before. According to the IMO, the combination of Emission Control Areas and rules limiting SOx emissions drove a nearly 30% reduction in SOx emissions between 2014 and 2017. We have seen markets and industries nimbly adapt to new rules. For example, in 2020, the IMO limited sulphur to 0.5% of fuel content by mass. Subsequent analysis shows that just 20% of fuel supply complied with the limit before the rules were enacted, but from 2021 to 2023, on average 80% of the fuel supply was compliant.

Meeting the new GHG emissions targets will rely on a package of measures regulating ship performance and GHG emissions, known as the short- and mid-term measures, together with guidelines on lifecycle analysis of emissions.

Short-term measures including the CII, which aims to increase the efficiency of the global fleet, were agreed between 2018 and 2023. The MTMs are currently under discussion at the IMO’s MEPC meetings. The MTMs aim to provide clear, strong, and binding incentives to transition the world’s fleet to cleaner forms of energy. The 2023 strategy committed to achieving this in a “just and equitable manner”, ensuring that the transition supports economic development in all countries while minimising risks to vulnerable groups, particularly in developing countries.

Fossil fuels are currently the cheapest fuels available because their prices do not account for their climate impact. As a result, sustainable marine fuels struggle to compete. Low fossil fuel prices lead to overconsumption and high GHG emissions.Ships therefore over-emit GHGs, and all suffer the consequences of climate change.

MMMZCS’s Fuel Cost Calculator, a techno-economic tool that aggregates data from experts across industries to predict production costs for a range of marine fuels, quantifies the cost gap between fossil and sustainable marine fuels using current and projected production cost estimates. Since these are production costs rather than market prices, they may be a conservative estimate of the ‘cost gap’ between sustainable and fossil fuels.

Fuel dominates the total cost of owning and operating a vessel over its lifetime (considering all future costs in today’s dollars). Analysis shows that owning and operating an 8,000 TEU containership over 25 years costs about US$ 200m. If the same vessel were a dual-fuel ship running on e-methanol, the cost of sailing the same route over the same period would be US$ 470m. Most companies cannot compete with costs 2.4 times higher than their competitors. Without policy, there is often no business case for decarbonisation.

Currently, IMO Member States are developing proposals for MTMs before evaluation in IMO meetings. These proposals vary in ambition and likely effectiveness but generally include five elements: the scope used to measure emissions, a goal-based fuel standard (GFS), GHG pricing, penalties for failing to meet the GFS, and flexibility mechanisms that reward ships going beyond the GFS.

- Scope: Legislating fuel emissions requires decisions about the ‘boundaries’ of emissions that can be attributed to fuels. The IMO strategy mentions that emission reductions should take into account well-to-wake (WTW) GHG emissions as addressed in the LCA guidelines, meaning the scope would include the full lifecycle emissions from feedstock to fuel production processes and their use onboard. Some proposals for the MTMs, however, focus on a tank-to-wake (TTW) approach, measuring only the emissions onboard the ship. Others call for a ‘TTW with sustainability criteria’ method that begins with TTW values but moves to WTW over time. The differences between these approaches are significant. For example, the emissions from ammonia produced from natural gas occur upstream and would not be counted in a TTW approach. Even looking at conventional fuel oil which represents 94.5% of the active fleet, the WTW emissions are 19% higher than TTW. Depending on how the targets are set, the choice of emissions scope could significantly impact the cost of compliance for fossil fuels. A TTW approach would allow fossil fuels to appear less carbon-intensive by excluding upstream emissions, reducing the financial incentive for companies to switch to cleaner alternatives.

- Goal-based Fuel Standard (GFS): Also known as a Technical Standard or GHG Fuel Standard, a GFS would limit the emissions per unit of energy, expressed as gCO2eq/MJ. Progressively tightening intensity targets would push companies to phase out fuels with higher climate impacts by exposing a growing share of emissions to a penalty.

- GFS Penalty: The effectiveness of the GFS depends on the penalties for non-compliance. The level of the penalty is critical because it will determine whether it is more favourable to invest in alternative fuels or continue business as usual and simply pay to pollute. A higher penalty increases the cost of sailing on fossil fuels, which, in turn, lowers the relative cost of sustainable marine fuels.

- GFS Flexibility: Some proposals include mechanisms that allow ships exceeding GFS targets to bank or trade their ‘surplus’ compliance, known as ‘flexible compliance’. Trading surplus can help sellers offset the higher costs of sustainable marine fuels, while buyers benefit by paying less than the penalty, diverting compliance spending to green technologies.

- GHG Pricing: Member States are evaluating proposals for a direct cost on each unit of GHG (that is, per tonne of CO2eq) emitted onboard. This has been called a ‘contribution’ because it would generate revenue that could be mobilised to incentivise sustainable marine fuels and technologies, offset the potential economic damage from higher shipping costs, be recycled back into communities and countries affected by the climate crisis, or some combination of these. Even modest GHG pricing would mobilise billions of dollars per year — particularly early on, when the industry will continue to rely on fossil fuels.

To incentivise decarbonisation, the various elements of the MTMs have to work together to make sustainable fuels and energy efficiency investments commercially competitive. If regulations fall short of making sustainable marine fuels cost-competitive, they could increase costs but fail to create incentives to meet the IMO’s GHG Strategy.

The primary risk that negotiators should seek to mitigate is ensuring regulations are ambitious enough to drive sustainable fuel uptake. A GFS with higher (‘stronger’) and lower (‘weaker’) penalty values will determine whether sustainable marine fuels become financially viable or if regulations merely increase fossil fuel costs without incentivising a transition. Under weak regulations, the industry might continue using fossil fuels and pay penalties, adding costs to shipping.

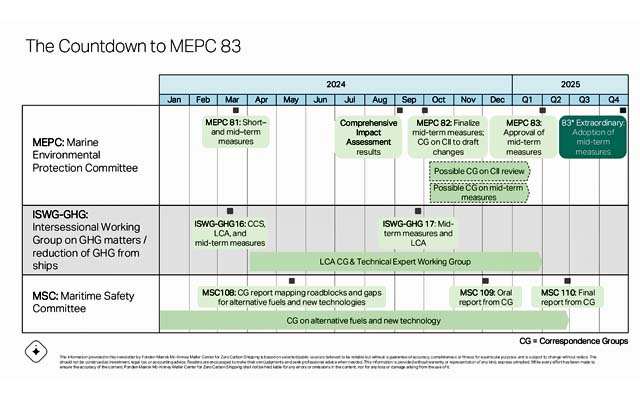

We face a tight timeline to agree on MTMs that can credibly deliver on the IMO’s ambitious strategy (see image). Critical meetings are scheduled for September and October, followed by a decision in spring 2025.

Image: The countdown to MEPC 83 (source: Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller Center for Zero Carbon Shipping)